THE CONTEMPLATIVE LIFE

The call of God can take many forms, indeed we can say that He calls each of us in unique ways to different tasks throughout the entirety of our life, so that we may give Him glory in a manifold way, testifying to His superabundant creativity like the animals and plants do in their nearly inexhaustible variety.

The call to a particular state in life is one of the ways in which God manifests this great creativity, for the Church is made up of many members, each reflecting a different aspect of God’s own essence and qualities. As Christians, we are all called to detach ourselves at least interiorly from the goods of this world. We are a people set apart and our God is a jealous God. Some are called to a deeper separation; in the Old Testament we see this with those that were to receive a special mission from God. The patriarch Abraham was told to leave his father’s house for an unknown land, Moses was taken out of Egypt and into the land of Midian, where he received the vision of the burning bush.

The examples of this call to separation are still more abundant in the New Testament. John the Baptist retreated into the desert to prepare for his mission, as did St. Paul after his conversion. Our Lord himself often sought out solitude far from the hungry crowds in order to spend entire nights in prayer.

Some souls are called to make a complete and permanent separation from the world in the religious life, which is designed to separate the heart from attachment to the goods of property, marriage and personal will. Among the religious, some are called to an apostolate ministering to souls. Others God reserves only for Himself, and these are the contemplatives, whose vocation it is to adore God in the silence of the cloister. Through their prayer and sacrifices, the contemplatives call down upon the world the heavenly dew that refreshes and sustains souls in their earthly pilgrimage. Without them, the world becomes a dried-up desert devoid of the water so necessary to life. The Church has always recognized this important function and encouraged the foundation of contemplative communities throughout the centuries.

Despite it being so necessary for the life of the Church and the world, the contemplative life is suffering in our modern times. There are fewer and fewer contemplative monasteries, many reduced to a trickle in vocations and seemingly destined to close when their last living members die out. New monastic foundations are essential to counter this trend and to refresh the weary face of the Bride of Christ. Our small monastic community was founded in an effort to help the Church rebuild her contemplative strongholds, so as to weather the storms of modernity and beat back its poisonous current.

THE BENEDICTINE CHARISM

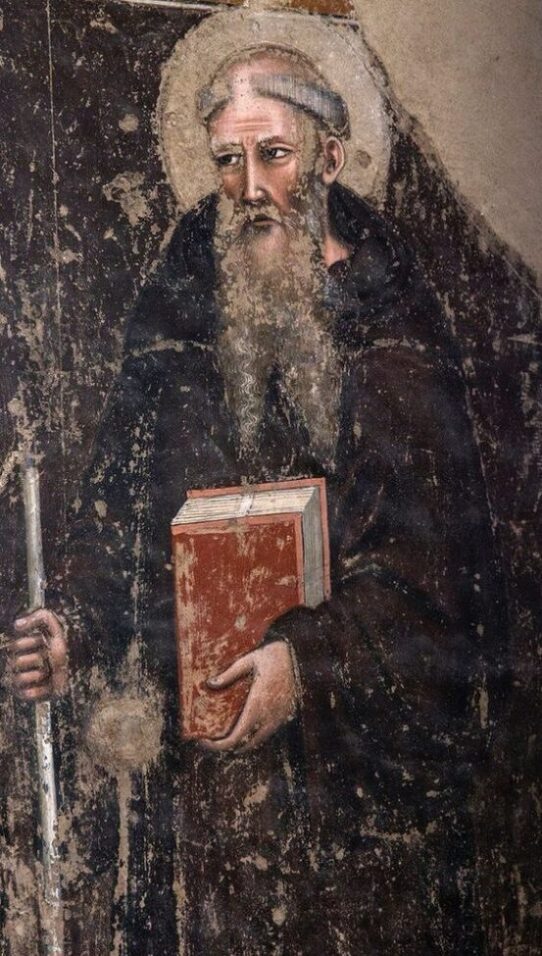

There are many rules approved by the Church for the contemplative life, each with its own distinct flavor. The Rule our community adopts is one of the oldest rules, perhaps the most widespread. It is the rule of St. Benedict, which was written in the 500s and has not ceased to inspire and instruct countless generations since.

The spirit of the Rule is best expressed by the motto often associated with the Benedictine order, the famous “Ora et labora”. Although Benedictines certainly do more than just pray and work, the saying expresses the principle that contemplatives should be occupied at all times but in varying ways, according to the needs of both soul and body. Everything in the Rule is ordered to make the contemplative life possible for men of ordinary strength and diverse temperament, and herein lies the secret to its success. Many have been encouraged to take up the yoke of religious life by the moderation and accessibility of the Holy Rule, which makes many concessions to the weakness of fallen nature without losing its crisp supernatural gaze.

The Rule is made up of different chapters. Some concentrate more on the interior life, such as the famous descriptions of the instruments of good works and the staircase of the degrees of humility. These concise but striking sections go straight to the heart and help the soul in building a solid foundation in the most common and important virtues. Other chapters focus more on the practical necessities of daily life in a monastery, such as what kinds of clothes to wear, what foods to eat and how to welcome guests. No detail escapes the watchful wisdom of Our Holy Patriarch.

The charism of the Benedictine Rule is simple, so simple that it may elude those searching for some elaborate, grandiose construction. In its essence, it is to form good Christians; well-rounded men and women capable of living a healthy supernatural life. Long before there was need of the doctrine of the Dominicans or the poverty of the Franciscans, the Benedictines were in the foundational business of forming balanced souls, so needed to build up the Church on solid roots.

In St. Benedict’s mind, the monastic community should be very much like a family; the abbot, a word which comes from the Aramaic “abba”, meaning father, and all his spiritual children, the monks. In the same way in which the natural family is ordered to foster the healthy development of the child, so the monastic family is meant to be the ideal environment for the growth of the supernatural life of grace. This is so important to the patriarch that he makes the monks take a vow of stability, which binds the Benedictine to the monastic community which he entered until his natural death. Within the familiar atmosphere of the monastery, the monk has the opportunity to learn and practice every virtue that the common life requires.

The monk must make two other vows, and they are conversion of life and obedience. Conversion of life is best understood as the daily struggle of the soul against its vices and imperfections. It is a constant turning away from sin and turning toward the Lord, to be enlightened and perfected by His light. This is often an uphill battle, for our nature easily turns downwards to the goods of this world and must be kept on the straight path through much effort and toil. Twice a day the Benedictine makes an examen of conscience, to better direct his energy in this work, which is often called simply the ascetical life. The ascetic battle goes on as long as we live on this earth, though with practice it becomes increasingly effortless as the soul grows closer to the fountainhead of all holiness, God himself, who will carry her through her daily tasks with His grace.

The vow of obedience entails a binding of the monk’s will to God through his superiors. The Rule makes it very clear that upon entering the monastery, the monk can no longer dispose of himself as he pleases. This vow asks the soul to give up her most precious faculty, her own will. This is meant as a remedy against the pride of our corrupted nature, by which we naturally seek to do our own will more readily than God’s. Through obedience, the soul is lifted from the multitude of pitfalls and dangers that come with trying to govern one’s self, a very perilous situation given our original corruption. The vow is thus meant as a penance of mortification but also as a spiritual aid in the path towards sanctity. By obeying our superiors, we are obeying the voice of God in our lives and are thus made similar to our Lord, who always and everywhere did only the will of His Father (“Not as I will, but as Thou wilt”, Matthew 26:39).

By walking the path of monastic life thus briefly outlined, the soul gradually blossoms and becomes immersed in an atmosphere of supernatural joy and love for God and neighbor, which completely transforms her and opens her heart to the wonders of God and the ardent service of others.

THE MARIAN FOCUS

Our founder Fr. Muard proposed the virtues of the Heart of Jesus and the Heart of Mary as a model for all the members of his community as an immense reserve of grace and love from which to draw the strength necessary to live a life “humble, poor and mortified” until the end of our days.

In the wake of this tradition, Dom Gerard consecrated his community and all its members “solemnly and irrevocably” to the Immaculate Heart of Mary in 1968, saying that Our Lady’s Heart perfectly embodies the two characteristics of the Work as imagined by our founders, namely interior life and immolation.

This consecration was renewed by Fr. Jehan for the foundation of our two monasteries of monks and nuns. In order to make more efficacious this consecration by which our communities became “absolute property” of Mary, we have also adopted the name of Benedictines of the Immaculate, so that our life of prayer, study and work can be so filled with the spirit of the Immaculate Virgin as to have Her alone live in us. We also wear the Miraculous Medal as part of our habit, an exterior sign that we belong totally to Mother Mary.

TRADITIONAL LITURGY AND DOCTRINE

The Benedictines of the Immaculate are deeply attached to the traditional liturgy of the Church. We pray the traditional Benedictine office in Latin, as it was handed down to us by our forefathers, and we celebrate the Mass according to the Roman Missal promulgated by St. Pius V in 1570, on the order of the Council of Trent, which has nourished the piety of countless saints over the centuries. The liturgical cycle is the essential spiritual nourishment of the Benedictine and we are determined to protect the wealth of riches contained within Tradition.

In a time of uncertainty and confusion in matters of doctrine, we have also chosen to nourish our minds and hearts with the most orthodox and certain sources, first and foremost the philosophy of being and theology of St. Thomas Aquinas, according to the prescription and recommendation of the Church for many centuries. We believe that a solid foundation is needed to overcome the poisonous precepts of the modern world, which seeks to corrupt even the most basic notions of common sense.